By Luciana Debenedetti

Starting the fifth day of our Humanity in Action fellowship by visiting the former extermination camp at Treblinka came as no surprise; for me, it was a strange combination of having the site and its history speak for themselves, and serving as a point of departure for our own discussions and interpretations so many years later. With our guide, Tomasz Cebulski, we first convened at Collegium Civitas to watch a very sobering film about the Warsaw Ghetto and the deportation of Polish Jews to Treblinka as part of Hitler’s Final Solution. We then boarded the bus to go to the camp. Writing this entry the day of our visit, with the experience and my feelings still fresh and exposed, I don’t fully understand what I saw, and I know that my thoughts in two days, three months, even five years from now, will be more digested, for lack of a better term. On the other hand, maybe this experience—this raw reality—is never fully digested or come to terms with.

I’ve already seen countless films and educational materials about the Holocaust, but being literally in Poland and knowing that we would be visiting an actual extermination camp shortly after gave me an unfamiliar feeling: being both fully conscious and nervous about what I was about to see, coupled with a subconscious numbing that prepared my mind for something no one is very ‘prepared’ for. At the end of the day, Cebulski posed the possibility that, as opposed to popular notions that the concentration and extermination camps are the prime example of inhumanity, they are quite human in fact..as it was fellow human beings turning on one another and thinking of these atrocious crimes. I’d never considered this reexamination of the definition, and this was not the only example of a term or idea that was turned on its head for me. In any case, I’m still unsure about the idea of equating these camps in any way, shape, or form, to “humanity.”

Throughout the day, we spoke extensively on the psychological and sociological mechanisms that existed in Nazi Europe…the conditions that exist for genocide: classification [to create an us vs. them situation], symbolization [to create stigmas], dehumanization, organization [for the mechanics of the operation], polarization, extermination, and, denial. It’s a difficult, unnatural, and uncomfortable task to try to place oneself ‘in the shoes’ of a perpetrator. The conditions for genocide show how susceptible people are to a system that overpowers, and strips them, of their own humanity—even though it is an idea that these same people created. The last stage—denial—which is carried out as methodically and intentionally as all the previous stages, for me truly cements the inexplicability of the mass murders and the murderers’ ability and necessity to detach themselves from the situation. Denying a murder devalues the lives of all those who were killed to the point of non-existence, both in their life and their death.

The bus ride to Treblinka was unassuming and ironic; it was a gorgeous, sunny day as we rode through the Polish countryside, finally arriving at a big forest. We uncomfortably joked that if we didn’t know we were going to a former camp, it could easily have been a hike or nature day to get away from the city. There are no traces of the actual camp now- the only thing that remains is part of the Black Road that connected Treblinka I (the lesser-known labor camp) and Treblinka II (the extermination camp). You just have to imagine.

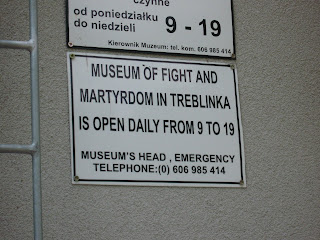

Before going to the cleared field and the former site of the chambers, we started at the “Museum of Fight and Martyrdom in Treblinka” on-site. The word martyr immediately struck me, and the use of the word came up later in our discussion. Is it because of its religious connotations? Does it give post-humus commemoration and a ‘reason’ for those who perished? Does it individualize those who were killed and force us to move past statistics? Is it a word that makes more sense in a Polish context? We didn’t really settle on an answer.

The site itself of the former Treblinka is extremely powerful: 6,000 symbolic stones representing Jewish towns or cities that were exterminated create a mass cemetery. 6,000 was also the approximate ‘daily capacity’ of the camp. The stones are placed on concrete ground, over the depositories of human ash and bodies. These sections across the huge field encircle the memorial: an enormous stone structure intended for the Jews of the Warsaw Ghetto, in particular. It’s a strangely eerie and beautiful site all at once.

We each walked around the site for about half an hour and reconvened later to reflect on the day and what we had seen. Group discussions are good opportunities for sharing your impressions and experience, but personal impressions are just as important here too. Cebulski told us that he never sets a ‘goal’ or ‘ideal’ outcome for his tour groups, just that every person gets something out of the day and is able to begin reflecting.

Seeing Treblinka means understanding the need to move from never forget to never again.

No comments:

Post a Comment